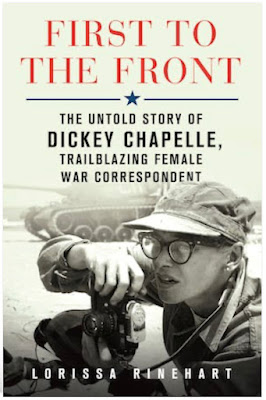

First to the Front: The Untold Story of Dickey Chapelle, Trailblazing Female War Correspondent

By Lorissa Rinehart

St. Martin's Press; hardcover, 400 pages; $32.00; available today, Tuesday, July 11th

Lorissa Rinehart is a cultural critic and historian who writes about art, war, politics, and the places where they intersect. Her writing has recently appeared in Hyperallergic, Perfect Strangers, and Narratively, among other publications, and she holds an MA from NYU.

First to the Front is the first definitive biography of photojournalist Dickey Chappelle, who from World War II through the early stages of the Vietnam War got her story by any means necessary as one of the first female war correspondents.

Chappelle went after dangerous assignments that her male colleagues wouldn't touch, and pioneered a radical style of reporting that focused on the humanity of the oppressed. She overcame discrimination both on the battlefield and at home, with much of her work ultimately unseen by the public until now.

Georgette "Dickie" Meyer was fascinated by planes from a young age, and she was one of only three women in the 1934 aeronautical engineering class at MIT in 1934 after she graduated two years early as the valedictorian from her high school in Sherwood, Wisconsin. Once in Massachusetts, she spent most of her time at Boston Airfield, as flying planes was more appealing to her than blackboard equations of force and lift. She flunked out of MIT, but she kept working at the airfield, and she became a fledgling teen reporter, pitching the idea of covering an airlift into Worcester, MA, where a historic flood cut off every road heading into the small city, for the Boston Traveler, a local newspaper that gave her the tentative green light. In order to get the story and secure publication, she had to make her way aboard one of the supply planes.

A few years later, in 1939, Dickey covered an airshow with worldwide implications at the Havana Airfield for the New York Times. That fall, signed up for photography classes with TWA's publicity photographer and World War I veteran Anthony "Tony" Chapelle. Dickey and her classmates practiced adjusting their f-stops and shutter speeds to capture traffic on the George Washington Bridge. Dickey and Tony were smitten with each other, and eventually get married, although it wasn't the most ideal, as the much older Tony made it clear to her that she would never be his equal and as she became more independent, he was more possessive. After they were married for 15 years, Dickie divorced Tony.

In January 1942, Tony shipped out of the Hudson River, as the Navy assigned him as an an aerial photography instructor at its base in Panama. As soon as he departed, Dickie began to pitch articles on American military operations in Panama to many publications, and eventually Look magazine assigned her to report on one of the military's lesser known war efforts in the Cenrtral American country. Prior to that, Look published her piece on women building war planes.

Chappelle went on to document conditions across Eastern Europe during the war, and was the first reporter accredited with the Algerian National Liberation Front, and survived torture in a communist Hungarian prison.

In 1961, Chappelle made seven jumps with the Vietnamese Airborne Brigade, slept seventeen nights in the field, was under fire seven times, and marched over two hundred miles through jungles and streams. She was on patrol with them on the Ho Chi Minh Trail along the Cambodian border, photographed them fighting with bravery and valor, and watched them die in agony before she got up the next day with the fighters, who began their battle again.

Some of the tactics Chappelle took for her journalism included diving out of planes, faking her own kidnapping, and endured the mockery of male associates before she died on assignment in Vietnam with the Marines in 1965. She was the first American female journalist killed while covering combat.

In this excerpt, Rinehard wrote of this trailblazer who was a witness and chronicler of history: "During the late 1940s, she witnessed the inception of the Cold War in the rubble pits of postwar Europe. Along with her then husband, Anthony 'Tony' Chapelle, she worked as a documentarian for numerous international aid organiations while living out of the back of a retrofitted baby food delivery truck for months at a time. In war-ravaged capitals, she interviewed families who made a home in former bomb shelters. In the countryside, she hiked miles to remote communities that had been all but cut off from desperately needed supplies. Few were willing to go to such lengths to demonstrate the true cost of international peace through international war, and perhaps more than any other single documentarian, Dickey captured a complete portrait of postwar Europe.

It was this unique vantage point that allowed her to analyze the emergent Cold War with an uncommonly nuanced understanding. While her contemporaries often described this conflict in outdated dualistic moralities of good and evil, us and them, the USSR and the USA, Dickey recognized the granular, human element at work within the wider geopolitical landscape. Having lived with the starving, the exhausted, the psychologically traumatized men, women, and children of postwar Europe, she well understood how the Soviets used the promise of peace and prosperity to tighten their vise grip of oppression. She was also one of the few to acknowledge the heroic strength of those who mounted yet another resistance to tyranny, even after so many years of hardship during World War II. It was reporting on this renewed fight for freedom within the context of the wider Cold War that defined Dickey's career.

Yet acting solely as a reporter and documentarian struck Dickey as increasingly insufficient as the Cold War progressed. More and more, she did what she could to directly intervene. Such was the case in revolutionary Hungary where freedom fighters battled a repressive Soviet-backed regime in the streets of Budapest. In the wake of this brutal urban warfare, thousands fled across the frozen tundra by night to Austria, and Dickey was there to cover this humanitarian crisis for Life magazine. But for all those fortunate enough to cross over, more were stranded just a few thousand yards form their goal, lost in the icy darkness or pinned down by machine-gun fire and tracer rockets. For weeks, Dickey ventured into Soviet-controlled territory to help guide these refugees that last mile of freedom.

Her bravery came at a cost. While trying to deliver lifesaving penicillin to resistance fighters, Dickey was arrested at gunpoint by Soviet border guards and held in solitary confinement at Budapest's infamous Fo Street Prison for five weeks. She emerged deaf in one ear and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Her devoted family as well as her own will helped her to recover in less than a year. But her experiences had changed her indelibly, and she found the fire that fueled her drive to document the fight for freedom for everyone, everywhere, burned with that much more heat. Simultaneously, the Cold War burst into flame across the globe through limited wars of independence. Dickey did whatever it took to get the story, every time, at any cost."

No comments:

Post a Comment