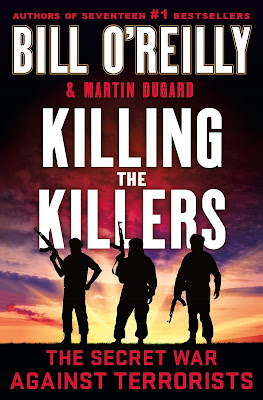

Swing and a Hit: Nine Innings of What Baseball Taught Me

By Paul O'Neill and Jack Curry

Grand Central Publishing; hardcover, $29; available today, Tuesday, May 24th

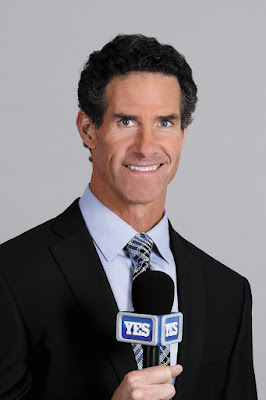

Jack Curry is an award-winning sports journalist who has been an analyst on the Yankees pregame and postgame shows on the YES Network since 2010, and is a winner of five New York Emmys. He covered baseball for twenty years at the New York Times, including as the Yankees beat writer in the 1990s.

Curry is the author of two New York Times bestsellers, Full Count: The Education of a Pitcher, with David Cone (click here for our coverage from 2019), and The Life You Imagine, with Derek Jeter.

In this new book from Curry, Swing and a Hit, which will certainly take its placeas a cherished baseball book capturing one of its most memorable players, he collaborates with Paul O'Neill on his memoir of his career, form his time with the Cincinnati Reds and leading the Yankees back to glory as one of the key parts of their 1990s dynasty. They are currently colleagues on the YES Network.

O'Neill also focuses on what he did as a hitter, how he adjusted to pitchers, how he boosted his confidence, how he battled with umpires, and sometimes water coolers, which Paul gives interesting insights into; and the advice he would give to current hitters. He recalls how he started to swing a bat competitively as a 5-year-old and kept swinging it professionally until he was 38 years old, when he retired after the 2001 season. O'Neill took a lot of inspiration from Ted Williams, who said using a round bat to hit a round ball is the most difficult thing to do in sports, and once received a call from The Splendid Splinter, which was filled with hitting advice.

I had the pleasure of chatting with Jack recently, and here is our conversation (lightly edited and condensed):

|

| Jack Curry. Photo credit: E.H. Wallop |

Jason Schott: Do you think Yankee fans, especially younger ones, remember, or comprehend, just what this team was like when Paul O'Neill was acquired in November of 1992?

Jack Curry: I can't get inside everyone's head, but I think the answer to that question depends on how young or how old we're talking. If you're 36 right now, that means when you were ten years old, it was Derek Jeter's rookie season, and Joe Torre started, you were used to that endless winning and World Series titles, so I do think when you've witnessed all that success, and been used to all that success, it sometimes is difficult to just go back a few years prior, as you mentioned, and having been a beat writer around some of those Yankee teams that really struggled and lost more than 90 games, I do think it is sometimes hard for fans whose introduction to the Yankees was '90s success to understand exactly where that success came from and how it was built because there were some lean years in there.

JS: It's funny you mention 36 years old as a barometer for a Yankee fan's view of the team because I am 37 and first really following the Yankees in 1993 when I was eight years old. In covering that team, what did you see in covering Paul in how he changed the tone and made that team a contender that season?

JC: When you watched Paul O'Neill's preparation and the way he approached games, and then the way he played in games, the word that you immediately thought of was intensity. Intensity and passion and the will to be a perfectionist, and as I got to know him, and got to talk to him about hitting, I realized that that was not a joke, that that's who he was, and one of the things we talk about in this book that I think is incredible, and he says it to this day, he never thought a pitcher got him out. He always thought that he made the out, and by that he meant, if he popped out on a low-and-away slider, his point was, at some point in his career, he took that low-and-away slider, drove it into left-center field for a double, so why did he pop this one out? He never wanted to give the pitcher any credit, and when we live in a world where we know what a .300 average is, you're failing seven times every ten at-bats, for O'Neill to take that approach I think it just speaks to that intensity, that passion, and that willing nature to try and be a perfectionist that he had.

JS: I forgot he flirted with a .400 average in 1994.

JC: It was an interesting season because, and I wrote this in the book, I'm pretty sure it was .400 into mid-June or something like that, and when we tried to talk to him that season, I don't want to say it annoyed him, but it distracted him, and Paul was not a guy who, especially before the game, and he would talk hitting with you - I have a line in the book where he says, 'I have to tell reporters nothing I say to you before the game is going to help me get a hit during the game,' and that was that fire and that intensity, again, that, I mean that was a huge story. You're in New York and the Yankees are turning things around, and here's this guy who has a swing that kind of looks like Ted Williams and he's hitting .400 deep into June, it was probably about 60 games into the season, so as much as I remember how hot he was, I also remember as a reporter trying to pin him down. I do think during that streak I did get him to sit and talk to me for 15 minutes once about hitting and I learned a lot about his approach there. It really was preparation, it really was taking a lot of swing;, he was never satisfied with the amount of swings he took before a game. In fact, he told me he would take outdoor batting practice with the Yankees, and if he didn't think his swing was right, minutes before the game, he would run down to the indoor batting cage because he didn't want to give that first at-bat away. That first at-bat might have been the chance to help your team win a game, you never know.

JS: That seems incredibly consistent with what one would expect of Paul O'Neill.

JC: Totally consisent with who he was, and that's why he and Don Mattingly jelled so well. He felt like Mattingly's work was his work, Mattingly's approach was his approach, and that they talked the ame language of hitting. They were superstar, All-Star type players who were also grinders. They didn't show up at the ballpark and think, 'okay, I got four hits yesterday, I'm good for today.' O'Neill got four hits and was thinking, 'how do I avoid going 0-for-4 tomorrow?'

|

| Paul O'Neill. Photo credit: E.H. Wallop. |

JS: The one thing that I think is unfair to Paul, and by extension Bernie Williams, was that when the Core Four phrase was conferred on Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte, and Jorge Posada in 2010, it kind of indirectly ignored their role in the dynasty when they were also a massive part of it. Where do you place Paul and Bernie in terms of how much of the dynasty they were responsible for?

JC: It's a great question, and I think the Core Four nickname is a wonderful nickname and I do think it groups those four players together perfectly, and they did play 17, 18 years together. I've always thought that Bernie gets the short end of the stick on that, and the way that I describe it is by using the words of the people who were there. Posada and Jeter have both told me that Bernie paved the way for them, and because a young player came up, and after some initial stuggles, found his way, that he made it easier for those that followed him because, maybe the Yankees, if Bernie had stuggled, would have traded one of those young players, and there were opportunities to do that. There was an opportunity to trade Mariano to Seattle at the start of the '96 season because they weren't sure if Derek was ready, so I think Bernie gets his due from the guys in the Core Four.

Then, as far as O'Neill goes, and I have this in the book, Don Mattingly, as respected as any Yankee in the last 50 years, he said that O'Neill was the one who created the sea change, and if you wanted to lokk for a moment where the fortunes of the Yankees changed, go back to that trade, go back to where the Yankees got O'Neill and he just wouldn't accept mediocrity, he wouldn't accept being average, so though they're not part of the fancy Core Four nickname, I think the people who were around and saw the development of what became a dynastic team, I think they all know what Bernie meant and what O'Neill meant.

JS: The fans know too, as proven by their overwhelming reaction to his number being retired, basically "about time," since they don't give the number out anyway.

JC: It's interesting, we completed the book in January and Paul got that call in Feburary, so I was excited for Paul as a friend and co-author, I was happy for Paul, but I immediately had to call my editor and say, 'we have a real-life version of stop the presses right here, we've gotta put this in the book!' and fortunately, we were at a point and there's a chapter, 'The Final Bronx Tale," it was a perfect place for us to tuck in his thoughts on having 21 retired. It did take awhile, you never how long or why these things take as long as they do, but as you said, it was almost as if the number was unofficially retired. The only player who ever wore it during the regular season was Latroy Hawkins, and he only wore it briefly because of all the fan blowback.

I know that Paul is beyong honored that that happened, and he actually told me that he and his wife were very teary-eyed when he got that call from the Yankees.

JS: He already has the plaque in Monument Park, but this seems a bit more valuable.

JC: Oh my gosh, yes, and I think once you get the Monument Park distinction and you get that plaque, and I'm not trying to get into Paul's head, you kind of think, 'well, that's the crowning achievement, I'm really excited and that's great.' There have been some players who have the plaque combined with a number retirement, so I think tehe fact that this finally came his way, now that's the crowning achievement. He said that it almost hit him really hard when his kids said - they all were sitting around as a family - and his kids said this is a legacy. A hundred years from now, some kind might walk into Yankee Stadium and say, 'hey Dad, how come no one's wearing number 21?' and that Dad will be talking about Paul O'Neill.

JS: One of O'Neill's biggest at-bats was in Game 1 of the 2000 World Series with the Mets, when he drew a walk to open the ninth inning against Mets closer Armando Benitez that started a rally to tie the game, which they went on to win in extra innings. How much of a turning point was that?

JC: I've had Mets people, and Al Leiter is quoted in the book talking about, if the Mets win Game 1, who knows where that series goes because there was pressure on the Yankees. The Yankees were the defending champions, they were the big brother to the Mets' little brother, andin a short series, if you lose some momentum at the beginning, who knows where that series is going to go, so I absolutely believe that if you look at the box score, and say it was quote 'only a walk,' that walk was as big as any walk I've ever covered or seen in my career as a journalist, and Paul kind of gets a kick out of it in the fact that he hit some postseason home runs, he had some big hits to help the Yankees win postseason games, but when he talks to people, a lot of them want to talk about that at-bat, that that's where their mind and their memories go, and when you think about it, that's pretty cool bevause he was really kind of a struggling player at that point, slumping, body didn't feel great, really thought thqat if Benitez threw three straight fastballs, he would might've been in the dugout after three pitches. Going back and watching that at-bat, I probably watched it a dozen times over again, and we talked about it a lot, I mean Jason, he was flailing at pitches, he was flailing at them to try and stay alive, and what I had forgotten about too was in the midst of that, maybe the sixth or seventh pitch, he popped the ball behing the third base dugout, and Robin Ventura almost made a miraculouys play going into the stands. He barely missed making a phenomenal play, which had he made that play, we'd be talking about that today not Paul's walk.

JS: I didn't realize Paul came up in 1985 in Cincinnati, with Pete Rose as his manager, but he really came alive as a hitter with another great Yankee who played similarly, Lou Piniella, took over in 1990, a year the Reds won it all.

JC: 100 percent, and that was something that was of interest to me too when we talked about this for the book. That's what I think is interesting about this book, and I've tried to reinforce that to people, yes, we talk a lot about Paul's career and all of his accomplishments and we get into some of the personalities of his family and things like that, but we also intersect all of the hitting influences, and the hitting stories that most impacted him throughout his career, so that's why you'rll hear about Rose and Piniella and Mattingly and Jeter and Ted Williams and Torre. That's where I had the most fun with this book, and I think that's part of the reason Paul was excited about doing the book. He, believe it or not, is not a guy who loves talking about himself, but I said to him, we're going to incorporate all the people who helped you, all the people you learned from, and even the people you might have taught something to, that's going to help other people, so that idea was attractive to him.

JS: It also illustrated how Paul's carrer bridged so many eras, from when Pete Rose was still active to joining a Yankees team that was in rebuild mode, and then the dynasty. It's an incredble career.

JC: Right, he touches the era of Pete Rose up to a Derek Jeter or an Andy Pettitte or a Mariano Rivera, and then mix in a little Ted Williams and Yogi Berra, so you've got a lot of different generations of baseball covered.

JS: One thing he stressed in the book and I love how you threw in that he told Kramer this in that famous "Seinfeld" episode, that he didn't view himself as a home run hitter.

JC: He says that, and he's not trying to, I mean the guy hit almost 300 home runs, but he always thought, if he hit a home run, it wasn't a mistake, but everything had to be perfect. He much preferred to be a guy who hit line drives, that's what he was trying to do. Now, homers happen - he hit a home run off Norm Charlton in 1995 in the playoffs that he absolutely to this day loves to talk about - but, right, he was a line drive hitter, that's what his Dad taught him when he was younger, and that's who he tried to remain for his whole career.

JS: I thought it was kind of pointed to today's players how he said, to paraphrase, 'I could never hit .200 with 200 strikeouts if it meant 40 home runs.'

JC: That would have kept O'Neill up at nights. I know that we are in a world in 2022 where strikeouts are more accepted and there are players who kind of fit that profile, but that was not who O'Neill ever wanted to be. He was about contact, and he did strike out a hundred times a couple of years, and that infuriated him...He talks about Ted Kluszewski in the book, he was one of his minor league hitting instructors, and if you look at Ted Kluszewski's numbers sometime, this guy was hitting 40 homers and striking out 40 times, I mean, that just doesn't exist anymore.

JS: After the success of your book with David Cone, how did this project come about?

JC: The same editor asked me if I had another idea, he said, 'I enjoyed working with you, let's do another book, and I gave him one idea because, again, I already ha kind of talked to O'Neill about hitting, and he said, 'I love that idea, let's do it,' and we jumped right back in. The writing and the reporting and all that is wonderful.

JS: What was similar and/or different about writing this book and David's?

JC: Similar; the book that was different, probably for me, was the Jeter book that came out in 2000, and only different in the way that, when we wrote that book, we were capturing Derek's life up to that point, but he was only 25 or 26. The Cone and the O'Neill books, these guys are in their mid-50s, and they've already had their career, they've been out of baseball for several years, and I think they have more perspective on their career. With Paul, I did all of the interviews either via Zoom or phone because of the pandemic. With David, we ended up metting and having some face-to-face interaction, which is always preferable. I sat down at my house and watched the perfect game with David, which is still a highlight for me as a journalist because he'd never done that before, but I never felt that just because Paul and I were talking on the phone that it was ever a hindrance. We know each other well enough that the conversation just flowed, and there were times when I would talk to him about a play or an at-bat, and either I would have it called up on YouTube or he might have it, or he might have looked at it previously. So, really very similar approaches to both books. This book was shorter, and that was intentional. The Coney book was over 400 pages, whereas this one we shot for a lower word count, this one was 240 pages, so it got done a little faster, but very similar experiences.

JS: David's felt more like a biography, whereas this one certainly is a biography, but it also had a lot of his thinking on hitting, like an attempt at Ted Williams' Science of Hitting.

JC: You're right, we did go a little more in-depth with David's career and some more personal stuff, and with Paul we mentioned it, but we kept it on the field more than we did with David, and tried to intertwine a lot of those hitting influences that I talked about, and also talked to some pitchers about Paul. Leiter's quoted, and Jesse Orosco, and Tim Wakefield, and I talked to some of Paul's teammates about him, so we just tried to make it all work whether you're a hitting fan, or a baseball fan, or a Paul O'Neill fan, or a Yankee fan, something that would be attractive to you.

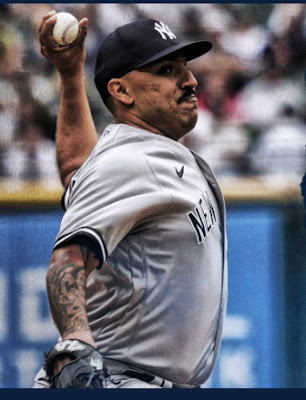

.png)

.png)

.jpg)