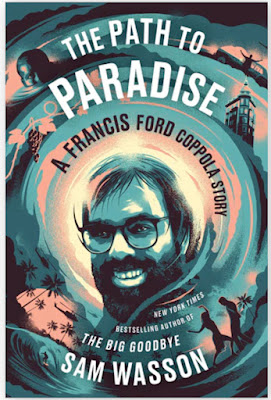

The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story

By Sam Wasson

HarperCollins Publishers/Harper Books; hardcover, 400 pages; $32.99; available today, Tuesday, November 28th

Sam Wasson is the author of six previous books on Hollywood, including the New York Times bestsellers Fifth Avenue, Five A.M.: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany's, and The Dawn of the Modern American Woman, and The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Days of Hollywood.

In the new book, The Path To Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story, Sam Wasson turns his lens on a true original, with this in-depth portrait coming ahead of the release of his long-awaited film, "Megalopolis" in 2024.

"They say you only live once. But most of us don't live even once. Francis Ford Coppola has lived over and over again," Wasson writes of one of the greatest filmmakers of all-time known for such classics as "The Godfather" and "Apocalypse Now."

The Coppola depicted here is a charming, brilliant man who is grounded in family and community, and at the same time, a restless, possibly reckless, genius. He has been on a half-century long quest to reinvent how films are made through his visionary production company American Zoetrope. It is a Greek term meaning "life revolution," and he brought the resources of filmmaking, business, technology, and the natural world to the stage in a laboratory of his own making.

Wasson writes, "Coppola initiated a colossal, lifelong project of experimental self-creation few filmmakers can afford - emotionally, financially - and none but he has undertaken."

That was shown in Coppola's very first feature film, "You're a Big Boy Now," which was released in 1966. He acted as his own producer, as far away from studio control as he possibly could, which was rare in that time. He envisioned shooting most of the film on natural locations, in the vein of the freedom and spontaneity of The Beatles' film "Hard Days' Night." Without introduction, Coppola approached stars Geraldine Page, Rip Torn, and Julie Harris and signed them on to the project, and the budget jumped from $250,000 to $1.5 million. A lot of where they shot the film in New York City was unprecedented, as they convinced Mayor John Lindsay to expedite permits to shoot inside the New York Public Library, which had a ban on filming, and the same thing with Macy's.

Wasson was granted unprecedented access to Coppola's archives, conducted hundreds of interviews with the artist and many who have worked closely with him, including Steven Spielberg, who said he was intimidated by the big ideas that Coppola and his colleagues had, along with talk of revolution. One of Coppola's main collaborators was George Lucas, the visionary of "Star Wars."

The story of how Zoetrope turned into a communal utopia is also the story of Coppola's wife, Eleanor, and their children, underscoring how inseparable each part of the filmmaker's world have been. Wasson also ties it into the creation of his quixotic masterpiece, "Apocalypse Now."

It also is part of Coppola's longing to finish "Megalopolis," which he has pored over for forty years. He has thought about it, quarreled with it, added to, and altered, and the story keeps changing. It is all in a quest to discover his signature mode of filmmaking. His whole career has built up to this moment, as "Apocalype Now" exposed him to the surreal, "One from the Heart" showed him a theatrical mode, and "Bram Stoker's Dracula," he drew on the live effects of early cinema.

Wasson writes in this excerpt: "Megalopolis is a story of utopia, a story as visionary and uncompromising as its author; more expensive, more urgently personal than anything he has ever done; and for all the reasons and too many others, nearly impossible to get made. In the eighties, when Coppola, felled with debt after Zoetrope's second apocalypse - the death of Zoetrope Studios in Los Angeles - was directing for money, he read the story of Catiline in Twelve Against the Gods, tales of great figures of history who, Coppola said, 'went against the current of the times.' Catiline, Roman soldier and politician, had failed to remake ancient Rome. There was something there for Coppola. Something of himself. What if Catiline, Coppola asked himself, who history said was the loser, had in fact had a vision of the Republic that was actually better? Throughout the decades, he'd steal away with Megalopolis, a mistress, a dream, gathering research, news items, political cartoons, adding to his notebooks - in hotels and on airplanes and in his bungalow office in Napa - glimpses of an original story, shades of The Fountainhead and The Master Builder braced with history, philosophy, biography literature, music, theater, science, architecture, half a lifetime's worth of learning and imagination. But Coppola wasn't just writing a story: he was creating a city, the city of the title, the perfect place. Refined by his own real-life experiments with Zoetrope, his utopia, Megalopolis would be characterized by ritual, celebration, and personal improvement, and driven by creativity; it had to be. Corporate and political interests, he had learned too well, were driven mainly by greed. And greed destroyed.

Over the years, Megalopolis grew characters, matured into a screenplay, tried to live as a radio drama and novel, and for decades wandered like the Ancient Mariner, telling its story, looking for financing, or a star: DeNiro, Paul Newman, Russell Crowe...The story of Coppola's story became a fairy tale for film students, a punch line for agents...and in 2001, paid for with revenues from his winery, it almost became a movie. On location in New York City, Coppola shot thirty-six hours of second-unit material. But after September 11, he halted production. The world had changed suddenly, and he needed time to change with it.

He passed the script to Wendy Doniger, University of Chicago professor of comparative mythology (and years before, his first kiss). She introduced Coppola to the work of Mircea Eliade - specifically, his novel Youth Without Youth, the story of a scholar who is unable to complete his life's work; then he is struck dead by lightning and rejuvenated to live and work again. Coppola, rejuvenated, made a movie from it. It was his first film in a decade. Thinking like a film student again, he kept making movies Tetro in 2009; Twixt, 2011 - modest in size and budget, fearing that Megalopolis, a metaphysical, DeMille-size epic, was and always would be a dream only, beyond his or anyone's reach. Utopia, after all, means a place that doesn't exist.

Then he decides to finance the picture himself, for around $100 million of his own money."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)