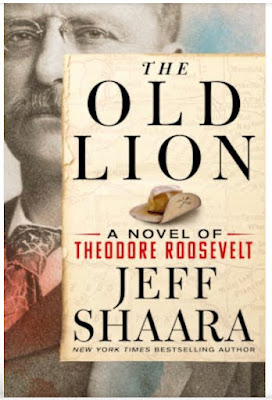

The Old Lion: A Novel of Theodore Roosevelt

By Jeff Shaara

St. Martin's Press; hardcover; $30.00

Jeff Shaara is an award-winning New York Times, USA Today, Wall Street Journal, and Publishers Weekly bestselling author of seventeen novels, including Rise to Rebellion and The Rising Tide, and two novels that complete his father's Pulitzer Prize-winning classic, The Killer Angels - Gods and Generals and The Last Full Measure.

With The Old Lion, Shaara brings to life Theodore Roosevelt, one of the most consequential figures in Americann history. He peels back the many-layered history of the man, and the country he personified, as well as looking at Roosevelt's life from his own point of view, putting the reader in his thoughts to see events directly through his eyes.

"Throughout the history of the United States, there have been presidents measured by their greatness or their mediocrity, their courage or their lack of courage during times of crisis, men whose decency or competence might place them a head taller or perhaps a head shorter than those who have come before them." Shaara writes. "Such lists are of course subjective, the stuff arguments are made of.

"This is the story of a president who would certainly appear on any list where greatness is a priority. That list is, regrettably, a short one, and includes Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and others over which you and I might disagree. But few, very few, would disagree that Theodore Roosevelt ranks high among the most revered, most respected, and most admired presidents in American history."

Roosevelt defined and created the modern United States. He grew up in the rarefied air of New York Society of the late 19th century, and he then spent time in the rough-and-tumble world of the Badlands in the Dakotas before he rose from political obscurity to become Assistant Secretary of the Navy. He then was turned into a national hero as the leader of the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War and rose up accidentally to become President.

Shaara reveals how Roosevelt embodied both the myth and reality of the United States, a country he loved and led. It is a novel told in an artful way as entries in a diary that keeps the narrative compelling.

In this excerpt, Shaara writes of Roosevelt just before his passing in early 1919: "December 1918 Oyster Bay, New York

His decline began months before, a recurring illness made worse by news of Quentin's death. His soon had been taken by the war, while in his glorious flying machine, this new tool of killing that so fascinated young men who knew nothing of their own mortality. Quentin had been shot down by his German adversary in July, a few months before the war had ended, one of so many, most of them unknown to any but their families. But Quentin's death made bold headlines. He was, after all, Teddy Roosevelt's son.

The impact on Roosevelt was mostly well hidden, some of his closest friends catching glimpses of sorrow, few ever seeing his tears in those quiet places where the grief overwhelmed him. But Roosevelt had a public face: politics and friendships and the adoring crowds. Among those who watched him closely were the men who kept to their high perches, and for them, there would be decorum, always. He was, after all, the man who established his own brand of decorum, his own manners and crusty habits, and for so long, all those important men, if they mattered to him at all, knew they could only go along for the ride.

Fewer still noticed that he had begun to slide, his energy ebbing, the speeches not as boisterous. If the crowds noticed, they might have seen that he was no longer the charging bull. But still they hallooed and waved and cheered him as in the old days.

Throughout the summer of Quentin's death, Roosevelt's grief was made worse by a deadly fear for his own three sons, warriors all in the Great War that only now had sent them home. There had been wounds and the agonizing viciousness of mustard gas, and despite his sons' reassuring letters that all were safe, Roosevelt, and especially Edith, still carried the fear that some horrible piece of news was yet to come. For her, it was a mother's natural anguish. For him, it became something very different, the blow to his emotions taking hold of old injuries, an unavoidable weakness that seemed to creep over him like a blanket of punishment. He had been so very strong, so active and robust, even in the later years as president and beyond. What the public could not see, and his friends denied, was the old leg injury, surgically repaired by frustrated doctors, the wound worsening and then healing yet again. It had occurred in 1902, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, his carriage in a vicious collision with a trolley car, killing his beloved bodyguard, Big Bill Craig. The damage to Roosevelt's shin bone had seemed unworthy of mention, and Roosevelt's own energy, still the speeches, always the confrontations with any challenge, had masked the pain and, ultimately, the seriousness of the damage. For years, infections followed, the pain rarely leaving him be. As he traveled the world, he fought to hide the limp, never speaking of such a weakness. But that changed in the jungles of the Amazon - another wound, in the other leg, striking him down with yet another vicious infection, made worse by his chronic malarial fever. In a place where healthy legs might ensure survival, Roosevelt hobbled his way through the worst conditions he had ever endured.

But now, with the Great War finally past, with his three sons safe, the loss of his youngest boy took hold even more. The grief and the injuries caused ailments that spread throughout Roosevelt's body, odd and varied pains, more desperate labor for the doctors. There seemed to be no cure for the torment, and by late 1918 the ailments had worsened, nearly paralyzing him. Despite optimistic reports fed to the newspapers, initially that he lay in a hospital bed suffering merely from attacks of lumbago and then later that he had surgery to correct a painful toothache, what the public would not be told was just how badly his spirit had been weakened. His body was losing the same fight. The pains and weakness were becoming constant, what his mystified doctors now guessed to severe rheumatism or gout or perhaps sciatica. The vertigo came now, confining him to his hospital bed. Finally, a string of good days, stronger, the vertigo gone, and when he insisted that he could manage, the doctors allowed Edith to take him home to Long Island, to his precious Sagamore Hill...

Through it all, he would not stop working, a source of frustration for those attempting to care for him. But his protests were obeyed. His letters went out, some across the Atlantic, to powerful friends and acquaintances in England and France, where the wrestling match had begun to settle the catastrophic costs of the Great War. It was no secret that Roosevelt hated President Woodrow Wilson, considered him a disaster for the nation's foreign policy, and was absolutely certain that Wilson's naked idealism and mindless ambition would accomplish nothing to heal anyone's wounds and might sow the seeds for yet another war. As Wilson sailed for Europe, expecting a triumphant reception from even the villainous Germans, talk grew that the president had a desperate fear that Teddy Roosevelt would return to the presidency in 1920. Roosevelt gave few hints about any such plan, despite the energetic push from so many in his party and from the public that he should run for office once more. But Roosevelt know his political life was past, that his ailments, the severity of the pains and the weakness, meant that his time was drawing to a close."

No comments:

Post a Comment