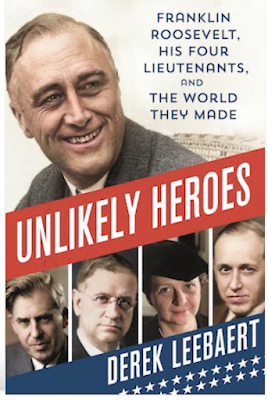

Unlikely Heroes: Franklin Roosevelt, His Four Lieutenants, and the World They Made

By Derek Leebaert

St. Martin's Press; hardcover, $35; eBook, $16.99

Derek Leebaert won the biennial 2020 Truman Book Award for Grand Improvisation, and he was a founding editor of the Harvard/MIT journal International Security and is a cofounder of the National Museum of the U.S. Army. His previous books include Magic and Mayhem: The Delusions of American Foreign Policy from Korea to Afghanistan and To Dare and to Conquer: Special Operations and the Destiny of Nations, which were both Washington Post Best Books of the Year.

In the new, engrossing book Unlikely Heroes, Leebaert examines how President Franklin Roosevelt chose to only have four people serve at the top echelon of his administration from the frightening early months of spring 1933 until he died in April 1945, which was when the United States was on the cusp of wartime victory.

Harry Hopkins. served as Commerce Secretary and a chief foreign policy advisor during World War II. Harold Ickes was the Secretary of the Interior for Roosevelt's entire presidency. Frances Perkins was the first woman to serve in a Presidential cabinet and was Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor. Henry Wallace served as the Agriculture Secretary from 1933-40, and then as Vice President from 1941-45.

These lieutenants were all as wounded as their polio-stricken titan, and they were strange outsiders. Until 1933, none of them would have been considered for high office, yet each of them became a world figure, and Roosevelt would have had a difficult time transforming the nation without them.

They composed the tough, constrictive, long-term core of government, and built the great institutions being raised against the Depression, implemented the New Deal, and they were pivotal to winning World War II. These Americans saved their democracy and rescued civilization overseas, and many of the dangers they overcame mirror those America faces today.

In this excerpt, Leebaert writes of Roosevelt's trusted advisors: "The best way to come to terms with Franklin Roosevelt, I believe, as well as to penetrate the maze of his presidency, it to take the synoptic view that arises from examining their lives. To this end, my book sheds new light on Roosevelt and on his dangerous times, and now is the moment to do so. The 2020s raise uncomfortable parallels with those most world-changing of years during the last century: social upheavals, climate extremes (the Dust Bowl), an urge to rebuild, and furious politics (the cry of 'America First' in both epochs), while world disorder threateningly increases.

Harry Lloyd Hopkins, son of an itinerant harness maker from Iowa, was forty-one when Roosevelt took office. He lends himself to fiction, as do all the others, but only Hopkins has figured in a novel - the Pulitzer-winning dramatist Jerome Weidman's Before You Go (1960) - as the thinly fictionalized Benjamin Franklin Ivey, the sickly, self-promoting assistant director of a settlement house who ascends ruthlessly from the Lower East Side to the peaks of decision-making in Washington. Such had been Hopkins's path in real life as he leapt from running boys' baseball games to being called the nation's largest employer as the New Deal fought overwhelming joblessness - and, even more surprisingly, to then becoming the president's 'Number 1 adviser.'

Yet Hopkins's self-destructive habits tore through his life; he also suffered from ulcers and the complications of a major cancer operation. Much of his death-defying agony could have been avoided. Nevertheless, his illness cast him as a grievously wounded hero who refused to leave the field. This became a source of power, and it drew him closer to FDR.

Harold Ickes, fifty-nine at the start, was the abused son of an alcoholic father. He had worked his way through law school to become a 'people's counsel' in Chicago for causes such as the newly founded American Civil Liberties Union and the city's Indian Right Association, which he organized. He had sought to be a kingmaker in progressive Republican politics, and failed humiliatingly. A long, wretched marriage to a rich divorcee only turned worse after he seduced his stepdaughter. By 1932 he was describing himself as a loser, continuously self-medicating a torturous insomnia and constant headaches with Nembutal and whiskey, his moods swinging between rage and unrestrained joy. Some days he literally could not speak. A white-shoe Wall Street lawyer he had never been. Roosevelt appointed him from nowhere to be secretary of the interior. This position merely became his base as he accumulated so many responsibilities - not least, as the country's unrivaled builder of public works, its 'Secretary of Negro Affairs,' its energy czar, and czar as well of all U.S. territories, such as Alaska - that he functioned basically as the chancellor of an ever-watchful monarch. He was the first U.S. official to be denounced by Hitler, in 1939, and he itched for war. Once it erupted, he proved a formidable war administrator, and central to Allied victory.

Frances Perkins, fifty-two, had known Franklin Roosevelt in the days when, she remembered, he could vault casually over a chair, like a 'beautiful, strong, vigorous, Greek god king of an athlete.' She reinvented herself as a Boston Brahmin, dedicating herself to God, to workers' rights, and to putting an end to the horrors of child labor. She brought Hopkins into Roosevelt's orbit and, in Washington, served as FDR's far-ranging secretary of labor. She was an essential force behind Social Security, minimum wage laws, unemployment insurance, and the rights of workers to organize. Less known are the terrible mistakes from which she saved the Administration and, because she also headed the Immigration Service, how hard she fought on behalf of refugees. As hostilities loomed, it was she who provided FDR with the sharpest assessments of the crumbling European balance. Then, often working closely with Ickes, she became pivotal to the war effort...

Henry Wallace, a crisp forty-five, was driven by an intellect The New York Times would describe as 'freakish.' Surely, he was the foremost agronomist in the Western Hemisphere, though his vibrant intellect was of a sort that left little room for human intimacy. He embodied intellectual strength but often failed to comprehend where that might take him, or the costs of his decisions.

For three generations, Wallace's staunchly Republican family had run the important weekly Wallace's Farmer out of Ames, Iowa. The Depression drove this paper into the hands of creditors while he was struggling to keep alive what today would be called a biotech startup.

Any man who combined brilliance, lonely idealism, involvement with the land, and being trapped was likely to appeal to Franklin Roosevelt. Wallace became secretary of agriculture at a time when nearly 30 percent of the nation made its living from farming. Then, in 1940, FDR told the Democratic Party Convention, in words conveyed through Frances Perkins, that Wallace would be his third-term running mate. For several years Wallace was a uniquely influential vice president as he rallied the country for war and then illuminated the vision of a postwar world worth fighting for."

No comments:

Post a Comment