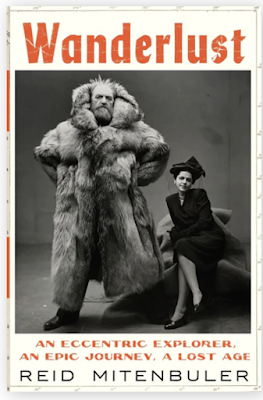

Wanderlust: An Eccentric Explorer, An Epic Journey, A Lost Age

By Reid Mitenbuler

Mariner Books; hardcover; $45.00

Reid Mitenbuler is the author of Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America's Whiskey and Wild Minds: The Artists and Rivalries That Inspired the Golden Age of Animation, and his writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Slate, and The Daily Beast.

Wanderlust is Mitenbuler's new book, and it is the story of one of the world's greatest explorers, Peter Freuchen, the real-life "Most Interesting Man In The World." This deeply-researched, entertaining work restores this heroic giant of the last century back into the public eye. It is an unforgettable story of daring and discovery, of restlessness and grit, and a powerful meditation on our relationship to the planet and our fellow human beings. It's also a story of the 20th century and the political, economic, and cultural forces that shaped that era. The story Mitenbuler tells of Freuchen ties these seemingly separate strands together, and brings alive a tumultuous stretch of history.

Deep in the arctic wilderness, Freuchen woke up to find himself buried alive under the snow. During a sudden blizzard the night before, he took shelter beneath his dogsled and became trapped while he slept. Now, as the feeling was draining out of his body, he managed to claw a hole through the ice, but he found himself in even greater danger. His beard, which was wet with condensation from his struggling breath, froze to his sled runners and lashed his head in place, exposing it to icy winds that needed only a few minutes to kill him. If Freuchen could survive that, he could escape anything.

Freuchen was a wildly eccentric Dane who had an insatiable curiosity that drove him from the twilight years of Arctic exploration to the Golden Age of Hollywood, and from the emerging field of climate research to the Danish underground during World War II. He conducted jaw-dropping expeditions, survived a Nazi prison camp, and overcame a devastating injury that robbed him of his foot and very nearly his life.

The life Freuchen led, at times humorous and heart-wrenching, was guided not only by restlessness, but also by ideals that were remarkably ahead of his time. He championed indigenous communities, environmental stewardship, and started conversations that continue to this day.

After spending more than a decade with the Inuit, as well as marrying an Inuit woman, Freuchen had a deep fondness for their culture. He then spent most of his life helping westerners empathize with them, especially as a changing world disrupted their unique lifestyle. He became aware of subtle changes in the Arctic climate that were altering life there. As early as the 1930s, he started to bring this information to other people's attention, although people weren't always sure what to make of it.

Freuchen's experiences came at the tail end of the "heroic age of exploration," as explorers competed fiercely for the final bits of glory in a world where exploration's last "big" achievements" were quickly being accomplished, such as the first to reach the world's highest peaks.

In this exceprt, Mitenbuler writes of Freuchen's reaction to seeing a death on the docks when he was a twenty-year-old medical student who had not been enjoying school to that point: "The dockworker's death, interpreted as a message from the Cosmos, forced Freuchen to realize something about his future. As he put it, 'I was not cut out to be a doctor.'

This realization was a long time coming. Freuchen's youth was spent stomping through forests, throwing things, splashing through creeks, looking for birds' nests, digging up plants to find their roots. He preferred the outdoors to classrooms, although he was never a poor student. He'd been a smart kid, an avid reader when the topic interested him, but he carried an inferiority complex regarding his academic abilities. These he later traced to his boyhood friendship with the genius Bohr brothers - Harald, who would eventually become a famous mathematician, and Niels, who would go on to win a Nobel Prize in physics and help establish quantum theory. Even though the brothers never rubbed his nose in their smarts, sitting in class with such brainiacs was like trying to swim in the frothy wake of an ocean liner. By the time Freuchen reached college, he was conditioned to feel out of place at school. He also looked out of place: a towering six-foot-five in his medical school class portrait, built like a bear, his unkempt hair a blond tornado. Not that a doctor needs to appear a certain way, but Freuchen couldn't help but seem destined for a different sort of life.

For Freuchen, the dockworker's death forced a reckoning. It made him ask what a future in medicine really looked like: Rise in the morning, go to work, do the rounds, go home, get up the following morning and do it all over again? To him, this was like living life in a circle instead of a line.

But what would he do instead? What did he love? Some of his fondest childhood memories were of the rowboat that his parents, Lorenz and Frederikke Freuchen, bought for him when he was eight. He had rigged it with sails and took it out on the waterways near his home of Nykobing Falster, a port town located about seventy miles from Copenhagen - a place of salty air, ringing buoy bells, sailors laughing at each other's stories. He loved the open water and the romance it promised. When Freuchen dropped out of medical school, he decided that some form of life at sea was probably a better fit for him. He just needed to find the right opportunity.

While Freuchen figured out what to do with his life, he explored different subjects offered at the University of Copenhagen and began spending more time with theater students, a group that shared his interest in performing. Before long, he fell into the orbit of a comedy troupe planning to do a satirical plat about the Danish explorer Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen, who had recently led an Arctic expedition and was now touring Copenhagen giving lectures about the experience.

As someone who had grown up reading explorers' memoirs the way a later generation would read comic books, Freuchen had already attended one of Mylius-Erichsen's lectures - and come away impressed. For someone like Freuchen - that is to say, a student struggling to avoid a mainstream existence - the explorer's appeal was probably enhanced by his anti-establishment vibe: he frequently wrote for Politiken, a prominent Danish newspaper, in ways that questioned polite society's beliefs about the church and the ruling classes. Mylius-Erichsen's bohemian outlook could also be detected in his most recent expedition, a two-year dogsled journey along the unmapped coast of northwest Greenland in search of inspiration for his poetry and prose - he called it the Danish Literary Expedition."

No comments:

Post a Comment