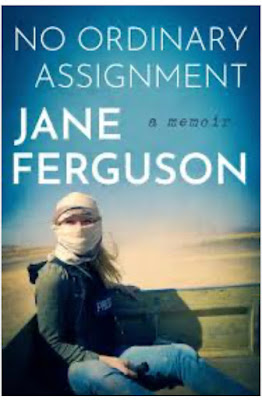

No Ordinary Assignment: A Memoir

By Jane Ferguson

Mariner Books; hardcover; $29.99

Jane Ferguson is a Special Correspondent for PBS NewsHour, a regular contributor to the New Yorker. and has been a visiting Professor of War Reporting at Princeton University. She is the winner of the Peabody Award, the Alfred I. DuPont-Columbia University Silver Baton, an Emmy Award, and the George Polk Award and Aurora Humanitarian Journalism Award.

"It takes a certain type of person to be a war reporter," Ferguson says. "We are complex, curious creatures with wandering souls and we are shaped and driven as humans and professionals beyond our grand ideals and neat, noble phrases. We are shaped by where we came from and, as we progress, by the things we have seen."

In her new memoir, No Ordinary Assignment, Ferguson chronicles her journey from bright, inquisitive child to intrepid war correspondent reporting from the front lines of the most dangerous conflicts and humanitarian crises of the past 15 years.

Ferguson grew up in Northern Ireland in the 1980s and '90s during "The Troubles," where war was a secret in her world. Bomb threats and military checkpoints were common, and an uncle's gunshot wound by an IRA (Irish Republican Army) assassin was disguised as a cow kick.

At a young age, Ferguson developed questions that cut through the culture of silence, while the unspoken tension in her village exploded into rage at home. An opportunity to study Arabic in Yemen came as a great relief, and began a new pursuit of answers.

Despite not having family wealth or connections, she rose up through the ranks of journalism while working as a scrappy one-woman reporting team, a borrowed camera often her only equipment. She reflects on what shaped her as a person before she was a professional, and how that guided her journalism. She unveils the dramatic stories and the dedicated storytellers behind the news.

In her illustrious career, she has reported from Yemen and Syria during the Arab Spring, Afghanistan while Kabul fell in August 2021, and Ukraine as Russia invaded in February 2022. While other reporters chased "bang-bang shoot-'em-up stories" that showed combat and its destruction, Ferguson sought out stories that gave faces and names to people experiencing these conflicts. In the face of grave violence, giving voice to civilian lives seemed a small act of justice, no matter the risks.

Ferguson had to also fight her own battles as a woman in a male-dominated field, from being told situations were too dangerous for her to cover and suggestions that she write softer stories aimed at a female audience. She always admired female journalists for their toughness, courage, and tenacity, and the reality of modern beauty standards unfairly factored into her advancement in TV news, and shaped her sense of her own femininity. Her story is one of being confident, flexible, resourceful, daring, compassionate, and authentic while facing uncertainty.

A Conversation With Jane Ferguson (provided by Mariner Books):

What inspired you to write No Ordinary Assignment, and why now? I wanted to answer the question Why Do You Do This Work? fully honestly. As I mention early in the book, it's posed to war reporters constantly, and I see myself and my colleagues tripping over answers. It's true that we find purpose in this work, that we believe in helping the world understand itself more, communicating a shared humanity in the worst of times, and exposing injustices. There is a certain justice to the recognition of someone that comes with listening to their experiences and stories and sharing them with others. That is all true.

But there is more to it than that. The answer as to how and why some people find home on the road, peace amid chaos, and a sense of purpose running towards situations and places most are running away from, is a deeply personal one. Those parts of ourselves are forged often long before we ever reach our first conflict zone. Many people have romantic notions of becoming a war reporter, having read Hemingway and pictured life on the road with a rabble of rebels, but only a certain set actually do it, make a life of it, and find a sense of home in it. And those people are shaped by more than their work. My book is an attempt to go back and connect those dots, to understand what makes someone do, and love, this work.

And why now? I reached a point in my life and work where I was finally able to sit, breathe, and take a break. I had been on the road for nearly fifteen years and was ready to step back. I was drawing a line in the sand, and although I'll keep travelling and working, I just knew it would no longer be my entire life. And yet, I didn't want to wait until I was too far from those years. I think everyone wants to get enough distance from a period in their life to understand it better, but not to be so far away it loses its gritty reality, the truth there not yet romanticized.

You grew up in Northern Ireland during The Troubles. Tell us a bit about what that was like and how it impacted your family. What was more pervasive in everyday life was sectarian division. Protestants and Catholics were living largely segregated lives. Towns and villages were either Protestant or Catholic, or divided clearly, each religious community's territory marked with flags and paint, British flags or red, white, and blue for Protestant areas, and Irish flags, or green, white, and gold, for Catholic areas. Children went to different schools, people drank in different pubs, businesses were Protestant or Catholic owned depending on the neighborhood they were in.

One thing I've come to learn over my years in combat zones is that to a child many things appear totally normal. That's how I feel when I look back at life there - that everything at the time seemed perfectly natural. I presumed everyone grew up with military checkpoints on the roads, 'bomb scares' when roads and businesses shut down following a false claim of explosives having been planted, and actual explosions.

My parents tried to shelter my siblings and I from the worst of the sectarian hatred, but they still had to exist within a system that didn't offer much of a middle ground. And my extended family were all Protestants, some of whom were members of the Orange Order, a Protestant organization dedicated to commemorating historic battlefield victories over Catholics. The Orange Order is particularly provocative and anti-Catholic.

There were few families in Northern Ireland not directly impacted in some way by the violence. My uncle who lived on a farm nearby ours had been shot by an IRA splinter group in an attempted assassination. He walked with a limp as a result. But Ulster Scotts culture is extraordinarily tight-lipped. We don't talk about The Troubles, we don't talk about bad things that have happened. My whole childhood I was told my Uncle walked with a limp because he was kicked by a cow.

When did you realize you wanted to be a journalist? Were you always inquisitive and tenacious, or did you need to hone those skills over time? I always knew this was what I wanted to do. I asked questions relentlessly as a child, so my nickname my parents gave me was 'Jane the pain' because I never stopped asking questions. And questions are not much welcome in stern, stoic, secretive Ulster Scotts culture. I was taken by the fact that women on the TV were asking questions for a living and, shockingly in the patriarchal culture, the men were answering them! Our culture in Ireland is also rich with storytelling, it's everywhere. That's a massive part of journalism. I also suppose my small-town girl's wanderlust impacted the kind of journalist I wanted to be more than I knew at the time. I grew up on a small farm in rural County Armagh obsessed with maps and Atlases and stories and pictures of adventures abroad. The world beyond those green hills felt so enticing.

You have reported form nearly every war front around the globe - from Yemen and Syria during the Arab Spring, Afghanistan during the fall of Kabul, and Ukraine during Russia's 2022 invasion. What was the most challenging assignment you've been on? In what ways did it test and stretch you? Covering the fall of Afghanistan was a story that stretched me more than any other, both physically and emotionally. I had never questioned my choices and struggled so much with what risks to take, how to assess danger, and what my role was (journalist or friend, humanitarian or writer, observer or participant?). Usually, I weigh risks and roles and decide how to proceed methodically and quickly, and I have many years and wars of experience doing so. When Afghanistan collapsed, everything I once knew and understood and could weigh up there vanished and operating alone just with my cameraman and making decisions for us meant deciding life or death choices with little context. I got on the last commercial flight that was allowed to land from Dubai that day, wracked with uncertainty about what I would land into. When I decided to stay on, while many were evacuating, or when we decided it was time to leave, each decision was tougher than any in my career.

The emotional toll of filming so many thousands of distraught people, begging me and my cameraman for help, stays with me. I had nightmares about it for many months after. I've never faced, in a literal sense, the devastating repercussions of the choices made in Washington DC on such a scale. Imagine thousands and thousands of people terrified for their lives, reaching through barbed wire, clutching their children, begging you for help, pushing their paperwork towards you, weeping. Some of them were my friends, and friends of friends, women in danger. I helped people get onto planes between working 20-hour days to put together extended coverage each night. We only had a Wi-Fi connection, our phones, camera, and laptop. Most nights I slept an hour and a half. I reached such a level of exhaustion and trauma I started getting sleep paralysis when I did fall asleep and had nightmares the Taiban were in my room (they were just meters away outside the perimeter of the building I stayed in). I lost ten per cent of my bodyweight in ten days. All the while, I was on air each night, trying to be articulate and communicate these peoples' stories as best I could.

Do you think that pulling our troops out of Afghanistan was the right thing to do? Are you concerned for the friends and sources who are still there? It's not my job to say if they should or should not be pulled out of Afghanistan, rather to help the public understand most viscerally the impact of decisions taken either way, especially on the local people there but also American and allied soldiers. What I wish had happened before (and would happen now), and what I tried to help, is a conversation more nuanced than simply to stay or go. I would like to hear people answer questions on the nature of leaving, what the plan was, what the strategy was, why were Afghans informed so late, why visa processors were not accelerated properly in the lead up. Why were US Marines left standing in the street, exposed to crowds, when everything collapsed? These are the sort of probing questions I asked and will continue to ask. It's my job to remember that no outcome is inevitable, that we don't have to accept a shrug from government officials, and that they owe the public and explanation for their decisions.

I am deeply concerned for contacts still there, and any woman in the country. The reality is the ability to help them has reduced to near zero now, and I struggle to know what to say to young women when they call me crying, saying they want to go to school.

No comments:

Post a Comment